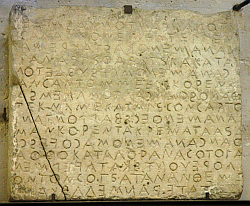

More than 2,500 years ago the people of the town of Gortyn in central Crete made an innovation that changed the world. The Greek citizens inscribed all the laws of their city on a public wall for any literate person to read.

This was a revolutionary act.

The Law Code of Gortyn

Bullies, in the playground or in public life, thrive on ambiguity. Bullies cannot act alone. They rely on the silent assent of the crowd. Ambiguity allows them to bend rules one way and later another, as the situation suits them. In an oral tradition the bully can exploit this. When laws are carved in stone a victim can point at the exact article that the bully is violating, and undermine the bully’s popular support.

In May 2013, Alan Shatter told RTÉ’s Prime Time that Mick Wallace had been cautioned by a garda about using his mobile phone while driving. Shatter, it appears, got the information from then Garda Commissioner Callinan, who may have gleaned it from the garda computer system, Pulse.

Unsurprisingly, Mick Wallace made a complaint under the Data Protection Act that this was a misuse of data. Shatter and Callinan are named in the complaint; the penalties are serious, up to €100,000 in fines.

Minister Alan Shatter and former Commissioner Martin Callinan

Data Protection Commissioner Billy Hawkes need fear no speeding tickets for the way he is dealing with the complaint. Eleven months after receiving it, the Bertie-era appointee was reported on Sunday as saying he will allow another month to see if Shatter and Wallace can settle the dispute ‘amicably’. Despite the simplicity of the case, Wallace has no chance of getting a ruling within a year of making the complaint.

Settling a dispute ‘amicably’ is a favourite of Irish authorities. It happens frequently in the courts, where huge pressure can be is put on parties to settle out of court; and it happens in all sorts of quasi-judicial situations such as the Data Protection Commission. It sounds good. Amicable. Friendly. Consensual. Progressive.

But it can also be a route to profound injustice. It is the job of the authorities to protect the weak from the strong. When authorities abrogate that duty, they leave the weak unprotected; we are left in a pre-Gortyn situation. The bullies can bend the law this way and that as suits their whim.

Martin Callinan described the use of Pulse data by garda whistleblowers to expose gross malpractice as ‘disgusting’. Exactly what disgusted him is unclear, as it seems he had no problem in tapping into the system to supply his mate Alan Shatter with tittle-tattle to smear Mick Wallace.

But Billy Hawkes wants this issue to be settled ‘amicably’, which means no formal decision, and no formal sanction against Shatter or Callinan. This is allowed for in law, but there is nothing in the Act that provides for cases to stretch over years to pressure someone to drop a formal complaint.

No doubt, part of this stems from pure laziness – it lightens his workload. Also, one tricky case off his books is one that is not going to be appealed, or draw criticism.

But pushing cases to be settled informally also means that those cases are more likely to be settled according to the power structures in society, not according to the law – it favours the strong over the weak.

This case is not a simple dispute between two people. It raises important issues about the separation of powers, accountability in politics and the public service, and the rights of citizens. It involves an allegation that two powerful individuals misused data to smear a political opponent. The suggestion is that an institution of state selectively leaks information to attack advocates of reforming that institution.

Mick Wallace has no right to authorise Billy Hawkes to wave aside these issues as though he were a rural sergeant waving on a local councillor driving home from the pub half-cut; and Billy Hawkes has no right to seek such authorisation from Mick Wallace.