Steve Garner is a researcher at the department of Social Science at Cardiff University. The BBC Analysis programme that he appeared in is available here.

*****

You’re used to me spouting on here based on not much more than my own prejudice, but here’s a topic that I am actually qualified to talk about. I studied linguistics, and I have quite a bit of experience in language learning.

And anyone who has learnt a second language – I’ll even count National School Irish in there – anyone who has learnt a second language will know that the words and phrases in one language often don’t map exactly to the ones in another. A language is a complete speech convention, it’s not a code. Things work differently from one language to another. Some languages have several non-interchangeable words where another language has just one or maybe none, and this can make problems for a language learner who hasn’t grown up with the experience of knowing when to use which word.

And this means that people familiar with language learners will quickly learn to spot what is the native language of the learner by the mistakes that they make in their target language, the language they’re learning. There’s even a name for it, it’s called native language interference. Believe it or not, this is useful when it comes to understanding the comments in the Daily Mail.

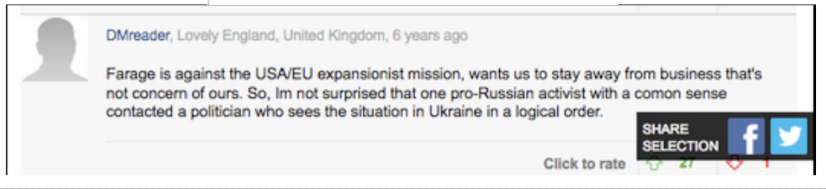

The comment was from someone with the username DMreader and gave their location as Lovely England, it was on an article about a request from a Russian-backed separatist in Ukraine to Nigel Farage to support his cause.

Articles, in case you’re not a linguist, are words like a and the. Actually, if you remember any of your Irish, you will be familiar with this. Irish has a definite article, an, the equivalent of the, like we say ‘An Taoiseach’. But Irish has no indefinite article, no equivalent for a or an. So, if you want to say ‘I ate the apple’ you say ‘D’ith mé an t-úll’; but if you want to say ‘I ate an apple’ you say ‘D’ith mé úll’. There is no translation of a or an, you just leave it out.

It’s easy to leave out a word that you don’t have a translation for, but if you’re an language learner, it’s much trickier to work out when to use words in your target language that have no equivalent in your native language, as the American-born comedian Des Bishop discovered when he learnt to speak Irish.

****

Now, here’s the thing about Russian. The Russian language doesn’t have articles at all. If you want to say ‘I ate an apple’ you say ‘Я съел яблоко’; if you want to say ‘I ate the apple’ it’s the same, ‘Я съел яблоко’, in both cases literally ‘I ate apple’.

For this reason, Russian learners of English have a the same problem Des Bishop had, with knowing when to use articles, knowing when not to use them and knowing which one to use. This might be surprising until you think just how complicated some conventions of English actually are. In theory you use the word the for specific things and a or an for non-specific ones.

But in reality, it’s way more complex than that. If someone says ‘I went to the bank’ or ‘I went to the beach’ it’s likely that they are not referring to a specific bank or beach, and sometimes we leave articles out altogether, and say ‘I went to school’ or ‘I went to work’. Sometimes this grammatical rule gets totally reversed. You might walk into a newsagent and ask ‘Do you have the Daily Mail?’, you use the when you don’t mean a specific one, you mean any of thousands that were printed.

Then go into the café next door to meet a friend, they ask you do you have a newspaper, and you answer ‘Well, I have a Daily Mail’ when in this case you are referring to the specific copy that you just bought.

It gets more complicated when you use negatives, sometimes the negatives can replace the article – ‘I have a computer’, ‘I have no computer’; and sometimes they can’t – ‘I have the book’, ‘I don’t have the book’. This makes things even harder for Russian speakers, because where English has several negating words, no, not, don’t and Russian has only one, нет.

This is where the comment by DMreader in Lovely England on a Daily Mail online article about Nigel Farage and Ukraine from a while back comes in, I’ll read it verbatim.

There’s a number of things there. Let’s leave aside the content, why someone in ‘Lovely England’ would be so concerned that the Nigel Farage take a stance on the conflict in Ukraine; let’s just look at the language.

“…stay away from business that’s not concern of ours…” That’s weird phrasing. You could say ‘not a concern of ours’, you could say ‘no concern of ours’, but ‘not concern of ours’ isn’t something typical of an English speaker.

Then there’s the mention of ‘one pro-Russian activist with a common sense’. With ‘a common sense’? Who says that? Not native speakers. And ‘sees the situation in a logical order’? that’s a strange way to put it, but it seems to me to be a direct translation of Russian phraseology. Not to mention that we are expected to believe that DM reader in Lovely England seems well-up not just on the conflict in Ukraine but also Farage’s position on it.

But I don’t.

Looking at the language, and I have significant expertise in this area, I haven’t a shadow of doubt that this text was written by a Russian-speaker. But here’s the thing. This text wasn’t written recently; it wasn’t ever written at the time of the UK Brexit referendum. It was written in April 2014, years before either that referendum or that presidential election. The Daily Mail online is the biggest UK online news source, and an obvious target for campaigns of influence.

They might have started sloppy, with writers who have middling English doing heavy-handed messaging, but it would be foolish to think they’ve given up on it, or not gotten better at it. Make no mistake, this is information warfare.

But it’s better than bombing Afghan wedding parties, I suppose. Or Malaysian airlines for that matter.