Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More

John McGuirk is the editor of Gript.ie

There is no doubt about the extent of the housing problem in Ireland, certainly not if you’ve been listening to this podcast, I’ve been banging on about it for longer than I, probably longer than you, care for.

And if you’ve been listening, you’ll know that I’m a sceptic about the more creative, more interventionist suggestions that are supposedly targeted at easing the crisis. There are two reasons why I don’t trust them. The first is that they generally don’t work – for example the focus on banning Airbnb, which sounds good, until you realise that, in Dublin for example, the number of houses or apartments on Airbnb that could potentially be released to the residential market is 253.

When you compare that to the 31,000 residences that the CSO records as vacant in the capital, it’s clear that’s a vastly bigger factor, but if you look at the relative amount of political comment and energy that goes into those two issues, there is a complete lack of proportion. On Twitter you see a huge amount of energy going into criticising Airbnb, and almost nothing about vacancy, and the same pattern is reflected across the political discourse.

I can’t quite work out why one topic gets far more attention than another that is objectively measured at more than 100 times greater – sometimes I begin to suspect that some dark political marketing agency is stoking up the Airbnb talking point to distract from the real issue, paid for by on the sly by people hoarding vacant land and housing, but that would be a bit too paranoid. Never attribute to evil anything that can adequately be explained by stupidity.

That said, it takes an awful lot of stupidity to explain an article in the Irish Times from before Christmas, which was headlined “Central Bank to consider ‘step break’ from mortgage rules”. The first two sentences of the article said,

Homebuyers earning less than €60,000 may be offered a “step break” from the Central Bank’s strict mortgage lending rules under a series of changes being considered by the regulator.

As part of a review of the measures, the Central Bank said it would consider a number of suggestions made to it … including loosening the current loan-to-income (LTI) and loan-to-value (LTV) rates for certain categories of buyers.

I was really shocked to read this, because what the Irish Times here is calling the Central Bank’s ‘strict’ rules, are the basic prudential measures that were brought back after the post-Celtic Tiger crash. During the boom, prices were driven higher and higher by people who could borrow more and more, and it all ended in tears.

The Central Bank started enforcing prudential rules which are designed to prevent banks from going bust, just after the banks went bust – people can’t generally borrow more than 3.5 times their salary, or 90 per cent of the value of the house they are buying. But now with property prices back to boom-era levels or higher, developers and banks seem frustrated that there is a limit to how deeply they can drive the ordinary punters into debt.

So I was surprised that the story by Irish Times journalist Eoin Burke Kennedy seemed to indicate that the Central Bank was minded to change the rules and bring us all back to the conditions that created the last great economic crash, and I got in touch with the Central Bank Press office to get more details about this, and the helpful people there sent me a link to the relevant press release.

And my next surprise was that the press release said nothing at all of what made up Eoin Burke Kennedy’s article in the Irish Times. No mention of relaxing loan-to-income or loan-to-value rates, no mention of looser credit for people earning less than €60,000.

So, I rang up the helpful Central Bank people and asked about this, and they solved the mystery. At the bottom of the press release were links to various documents, including a 28-page summary of the Central Bank’s Listening and Engagement Events – this is standard fare for government bodies, they invite comments on their work from anyone who is interested, and the sake of transparency, the Central Bank publishes a summary of the feedback they get.

And there are a few lines on page 19 of this document, where they report feedback that some unnamed participants were worried that the lending rules would make it challenging for single people, lone parents, and average income earners to buy a house, and the solution would be to wave aside borrowing limits and let them drive themselves further into debt.

We don’t know who these participants were, and we don’t know if those participants had any concern for the welfare of hard-pressed millionaire bankers and developers, into whose pockets all that extra borrowed money would go.

We also don’t know why Eoin Burke Kennedy chose to take a random anonymous comment 19 pages into an obscure 28-page document and make it into the first sentence of his Irish Times article, saying “Homebuyers earning less than €60,000 may be offered a “step break” from the Central Bank’s strict mortgage lending rules under a series of changes being considered by the regulator”, as though this was a policy change being actively considered by the Central Bank.

And, we don’t know if some banking PR consultant obligingly drew Eoin Burke Kennedy’s attention to this line and helpfully suggested he make it the lead in the story that he was writing. We don’t even know whether the Irish Times’ dependence for its survival on property advertising flickered across Eoin Burke Kennedy’s mind when he wrote the article.

What we do know for sure, and we know it from bitter experience, is that pumping even more money, from whatever source, into Ireland’s already over-inflated property market is not the way to solve Ireland’s housing crisis.

Sadly, the answer to Ireland’s housing crisis is boring and simple and unpopular. We need to build high-quality, high-density housing in the right places, and shift a portion our tax base away from income and onto property to penalise vacancy, hoarding, and dereliction. And, sadly, almost all our political parties are against that because that would upset vested interests. And, sadly, the public support them on this, because it’s always easier to campaign against a new tax, than it is to explain why it would benefit people; and there’s always more ‘locals up in arms’ objecting to a new development than there are people supporting it.

So, when I saw various demands to ban Build to Rent, BTR, I didn’t take them very seriously. Schemes that try to make housing available only to one type of buyer, by excluding other buyers, with the purpose of favouring one group – first time buyers, or Irish-speakers in the Gaeltacht – these schemes almost never work. Housing is basically fungible; that means that a house is a house, any house or apartment you build is one less family that needs to be housed, and even if it was a good idea, which it’s not, you can’t really enforce rules advantaging one group over another without rules so stringent as to be impossible in a democracy.

If you say that only this type of person can buy this house, or can buy it at a discount, either that means the buyer doesn’t really own the house at all because they’re not allowed to sell it, or you get the problem of a straw-man buyer in between or someone who is allowed to buy the house just flips it or rents it immediately.

So, with the Build to Rent, what does it matter if it’s to rent or for an owner-occupier, market forces are going to determine that anyway. But what I didn’t realise until it was pointed out, was that Alan Kelly, now the Labour Party leader, as minister for the Environment, gutted the upgraded building regulations that his predecessor John Gormley had brought in, and that allowed Fine Gael housing minister Eoghan Murphy, before he jetted off to Armenia with the OECD, it allowed him to create a special category in the building regulations which govern Build to Rent.

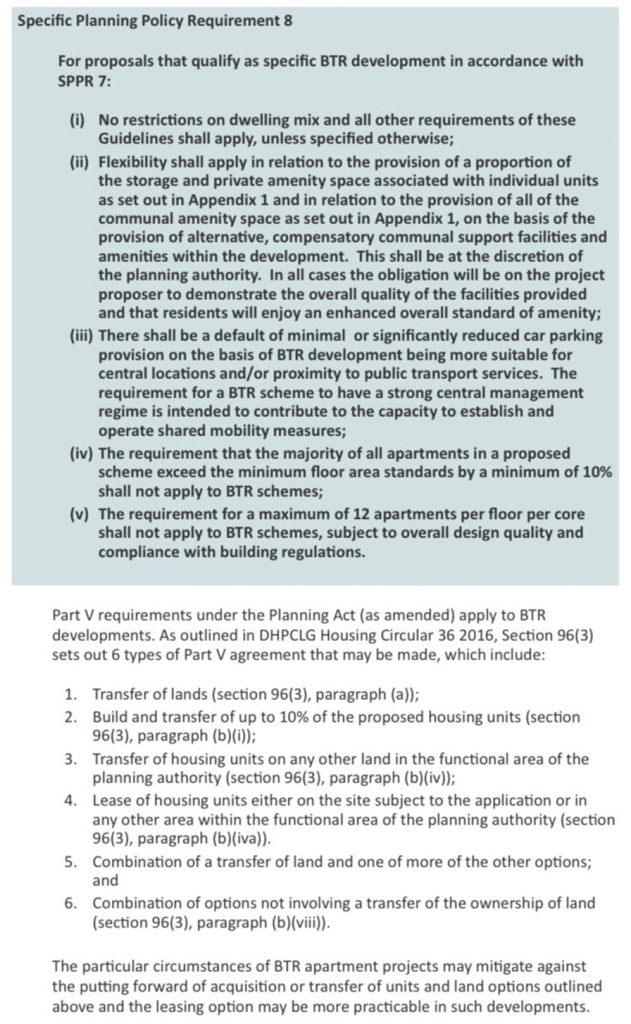

This means that when you build an apartment block, the law says that you must have this many two- and three-bedroom apartments, only a certain ratio of one-beds and studios, and they must each have a certain minimum floor space, and various other regulations about enough windows, enough parking spaces, the amount outdoor space, and how many apartments are allowed for each separate entrance. If your design doesn’t meet those standards, you don’t get permission to build it. End of story.

Except not quite. If you classify your block as BTR – Build to Rent, then none of these regulations apply.

This is insanity.

This is literally madness. What happened next was what was blindingly obvious would happen next. Developers had the choice between meeting the standards to build decent homes, or slapping up as many shoeboxes as they could fit on the site, with so few windows that you have to leave the lights on all day, with no parking spaces, with nothing resembling a garden, and with hundreds of apartments using the same door so you never seen the same neighbour twice, and the loss of security and community that goes with that.

To the shock of nobody at all, they chose the option that would make them twice as much money for half the investment.

Now, I should note that there are some commentators who say that all housing should be built like this, they say that regulations specifying decent conditions are what are keeping prices up and causing the problem. They are basically saying that the housing crisis is caused by the unreasonable and irrational demands of Irish people who for some strange reason don’t want to fry onions, iron clothes, change nappies and sleep all in the same room. I’ll talk to those commentators after they live with their families in a BTR unit for a few years. And when I talk to them, I’ll explain that prices are governed by supply and demand, or in this case lack of supply, not by input costs.

The collapse of the apartment-building sector into the sewer of neo-tenements is as complete as it predictable. Since the regulations were changed the proportion of all apartment schemes that are classified as Build to Rent has gone from practically nothing to 95 per cent, and even in this necon’s wet dream of a regulation-free wild west, prices have gone up and up and up, because prices are governed by supply and demand, not by input costs.

It goes without saying that the exemption from so many building regulations was something ferociously lobbied for by the building industry. But governments and ministers are lobbied for all kinds of things all the time. Alan Kelly and Eoghan Murphy agreed to this. They made it law. Most recently we know that the current housing minister, Fianna Fáil’s Darragh O’Brien has scrapped the completely uncollected seven per cent derelict sites tax – Fianna Fáil had proposed in their manifesto to increase it to 14 per cent – instead, they have scrapped it in favour of a vague promise to introduce a three per cent tax, which they really, really promise to collect next time, but not before they’ve had a few years to study the issue, and almost certainly not until after the next election, and shur who knows what will happen then.

We know from tribunals that in the past, planning law and planning decisions have been changed in return for bribes. As I said you should never attribute to evil anything that can adequately be explained by stupidity. In this case, it seems very much that stupidity is not an adequate explanation.

Thanks to Alfonso Bonilla for help with this.