Podcast: Play in new window

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS | More

Holly Cairns is the Social Democrats spokesperson on agriculture, food and the marine, and further and higher education and disability.

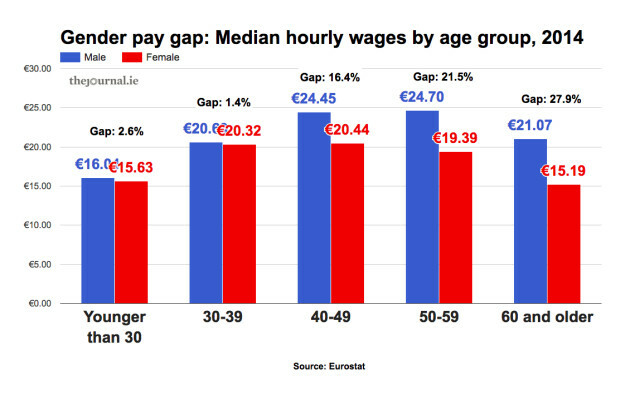

In the interview, Holly questioned the source of figures that indicated that the difference in earnings between men and women was concentrated in the over-40s, with no statistically-significant difference in earnings for those under 40. This information comes from the same Eurostat studies that Holly draws her 14 per cent earnings difference from; the Journal have an excellent article on it here, which includes this graph:

The same article notes that among full-time workers:

women, on average, work fewer hours each month than men – 129 as opposed to 149.

So men work 20 hours more per month, almost exactly one hour per day. That creates a difference between the gender earnings gap and the gender pay gap – with the latter adjusted to reflect the difference in working hours.

Figures on the pay gap are sometimes also adjusted to account for qualifications and years of experience, but are generally not adjusted to reflect what happens during those years, such as the difference in working hours.

As Holly noted, all these figures are typically calculated based on full-time workers only, bypassing the fact that part-time work is dominated by women.

The most dangerous professions, as calculated by the US department of Labor is as follows:

*****

I try to steer away from jargon on this podcast, but I’ve got two jargon words to give you here. The words are MUP and BOGOF.

Before I tell you what those mean, let me apologise for the background noise. I’m not in my usual little back bedroom improvised studio at the moment, I’ve managed to get away, so I’m complying with all the covid regulations by self-isolating by the seaside. On a small Greek island. Good weather, nice beaches, small taverns, cheap wine. Try not to be jealous.

But maybe you should be a bit jealous of the cheap wine. That brings me to MUP, that sands for minimum unit pricing, the unit in question being a unit of alcohol. The cabinet recently signed off on proposals to bring in minimum unit pricing from next January, so that there will be a floor price below which alcohol can’t be sold to consumers.

Because alcohol is much dearer in pubs, when we have pubs, this really just affects off-licences and supermarkets that sell wine, beer and spirits. This idea has been knocking around for a while; it first came to prominence in Ireland in the 2011 Fine Gale manifesto, I’ll read what they said verbatim:

Supporting Irish Pubs: Fine Gael recognises the importance of the Irish pub for tourism, rural jobs and as a social outlet in communities across the country. We will support the local pub by banning the practice of below cost selling on alcohol, particularly by large supermarkets and the impact this has had on alcohol consumption and the viability of pubs.

‘The viability of pubs’ – so, it was clear that this was a measure to support the viability of one business at the expense of another. Publicans, who make vast profits, have huge political power; quite a few TDs are publicans themselves. Industry sources that I’ve talked to say that pubs typically make gross margin of 50 per cent or more on the drink that they sell.

If any other industry had that type of margin, there would be rush by entrepreneurs to get into the market to cash in on those profits, and that competition would bring down prices and profit margins. But there is no rush of competition for publicans because they use their political muscle to get the government to make it illegal for you or me to open a pub. You need a licence; the number of licences is strictly controlled, if you want one you have to pay, probably millions, to buy one off someone who already has one. It is a classic government-enforced cartel.

The effects of this cartel are pretty obvious to anyone who has spent time at a Mediterranean resort. Like pubs in popular Irish locations, the bars in Greece, Spain and so on often hire staff to stand outside the door to interact with potential customers.

The difference is that on the continent, they hold out menus, talk up the fare on offer, bring people in, find them a table and so on; their job to get people into the pub. In Ireland the job of the door staff is to keep people out. Think about that for a minute. What other business is in a position to hire staff to keep potential customers away?

And think about what those continental door staff are doing for a moment – offering food, making sure people find seating and so on. The food in Irish pubs has improved in recent decades, but there are still plenty of places that offer nothing, or next to nothing other than alcohol. This is a totally standardised product, it’s almost impossible to go wrong. Restaurants are subject to the whims of taste and fashion and go in and out of business at regular intervals.

Pubs, by contrast can do the same thing year in, year out, making huge profits as they go, guaranteed that nobody can come and compete with their business – so they have plenty of time and money to devote to political lobbying to make sure that their little goldmines aren’t interfered with.

The only fly in the ointment for them was that they were making so much profit that their customers were increasingly staying at home and having friends around for a few drinks, bought much cheaper in a supermarket or off-licence.

That was the context of Fine Gael’s 2011 promise to recognise the importance of the Irish pub, as they put it, by restricting competition from off-licences and supermarkets. This didn’t really go anywhere because, despite pressure from the publicans, there wasn’t really any evidence that much of the alcohol sold was sold below cost, those guys are in business to make a buck too.

But that protectionist measure has now come back like a zombie in the guise of a well-intentioned social reform supposedly to reduce alcoholism, setting a minimum price, below which alcohol cannot be sold. A similar law is already in place in Scotland, but the minimum price per unit of alcohol there is set at 50 pence sterling, the equivalent of 57 euro cent; the Irish level is being set at €1 per unit, almost double the Scottish price.

Just in case you are wondering, this is not a tax. All of the price increase goes straight to the retailers and producers of the alcohol. And the price hikes are going to be pretty steep, the minimum price, the lowest possible legal price for a bottle of wine will be about €7.50, the lowest possible price for a can of beer will be about €1.70.

To put that in context, I went into a supermarket where I’m staying in Greece the other day, there were cans of beer for 69 cent, bottles of cheap Greek wine for 99 cent and plenty of other wine choices for under two euro. Prices in Ireland are already far higher than that; come next January they will be much higher still.

So the question is, does that lower price lead Greece to have more alcoholism than Ireland? No. Even with the current pricing structure, where Ireland has some of the most expensive drink in the world, we are very close to the top of the world league in alcohol consumption. According to the World Health Organisation, there are only six countries on earth where people consume more alcohol than us; we drink well over double the global average.

Mediterranean countries where alcohol is dirt cheap come way down the table, Greece at 34, Italy 48.

Now I don’t want to say that there is no evidence that price has any impact on alcohol consumption; there is. In Finland, they had very high alcohol prices but cut them sharply in 2005 in anticipation of Estonia joining the EU and making cheap booze just a short ferry ride away. There was a noticeable increase in alcohol-related harm, such as admissions to accident and emergency wards.

There have been studies on this, the minimum pricing in Scotland also seems to have had some effect in the opposite direction, but it’s not clear yet whether in either case this is a cultural shift, or a short-term effect, and whether the previous patterns will reassert themselves. It is plausible that this would have some effect on young people drinking, price can be a real barrier for them, but it’s naïve to assume that this would have much impact either on alcoholics or even on occasional binge-drinkers. Price just doesn’t seem to be a barrier for them.

But one thing that, as far as I can see, all of the research is whether or not the MUP would reduce the problem of over-consumption of alcohol. Nobody is studying whether it could make the situation worse.

Very basic economics imagines that there is a straight-line relationship between price and consumption. That’s often true, but not always. There are examples of what are called inelastic markets, that’s to say that however high the price goes, people will pay it. A good example of this is booze for an alcoholic – they will pay what it takes to get their fix.

But there are also examples of markets where, when the price goes up, people buy more. This is counterintuitive, but humans aren’t always rational. One example of this diamonds, which the marketers have managed to persuade people that are some sort of age-old tradition, but really only became a popular option for engagement rings since the Second World War; and a key part of the marketing strategy was to massively increase the price; making people feel the product must be important, since it’s so expensive.

This is a great trick, if you can get away with it. People buy more because you are charging them more. Not just jewellery, it can also work with cars, some food items, particularly luxury foods – would anyone really want oysters if they were 99 cent for a 10-pack in Aldi? And there is evidence that it works with alcohol.

Now the real giveaway that this is a protectionist measure that has nothing to do with public health is that the price is not being increased by a tax, it is being increased by outlawing price competition; all of the extra that you will pay will go straight to the retailers and suppliers.

They will be coining it. The worst possible thing that could happen for them is that they have slightly reduced sales rewarded with massively increased profit margins. But I’m not at all sure that the sales will be depressed for long.

In modern marketing, aside from higher prices sometimes actually stimulating higher sales, retailers have a whole host of devious ways to trick us into buying more than we really want. That brings me to BOGOF. That stands for Buy One, Get One Free. If you look around your local supermarket you will notice that you don’t seek 50 or whatever precent off any more on many products. Instead, you will much often see Buy One, Get One Free. That’s objectively a worse deal for consumers, you have to buy two products to get the discount. But the retailers have worked out that consumers subconsciously saw the lowering of price as a signal that it was a lower-quality product.

The same thing, but phrased differently, with a requirement to buy two units – Buy One, Get One Free shifts far more units and makes far more profits.

Now that retailers will have much bigger profits, they will also have the cash and the motivation to work out devious marketing tricks to persuade people to buy more booze. It might take them a while, but with such huge profits to be made, and a guarantee that nobody can undercut them on price, you can be sure that they will work it out.

I doubt if this measure will do much for alcoholism in the long term, but you can be certain that it will create another entrenched politically-protected cartel, and that’s not a good thing.